In race for mayor, top spenders in Mass. often have an edge

Published March 30, 2017 in The MetroWest Daily News

NEW BEDFORD — When she returned home three years ago, New Bedford native Maria Giesta found a city still struggling to meet its potential.

The first member of her family to earn a college degree, Giesta spent much of her career working in the nation’s capital as a staffer for U.S. Rep. Barney Frank.

When family ties brought her back to New Bedford in 2014, Giesta said she observed many of the same challenges she remembered as a child — crime, drug addiction, the need for new jobs — and felt compelled to help.

She decided to make her own foray into politics, setting her sights on the city’s two-term mayor, Jon Mitchell.

“I thought that running for mayor I could have done a lot of good things for the city,” she said, “especially with my connections in Washington D.C., and just knowing how the process works.”

Giesta entered the mayoral race in dramatic fashion in January 2015, announcing she would fire the police chief if she unseated Mitchell in the fall. She hoped the coverage of her fiery announcement would be a springboard to discuss other issues.

But her experience over the ensuing months was an “eye-opener,” Giesta said, not only into the power of incumbency, but also the role of money in local campaigns.

As a sitting mayor, Mitchell naturally enjoyed higher visibility, but also benefited from incumbency in subtle ways. He was a frequent commentator on the local radio station, for example. And local Democrats lined up behind him, Giesta said, excluding her from some events.

With support from former colleagues in D.C., and dipping into her own savings, Giesta mustered enough money to make the race “competitive,” she said, paying for some advertisements and campaign signs. But Mitchell trounced her in the air war; in the month before the election, it felt like his ads were playing each time she turned on the radio, an important vehicle for reaching Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking voters.

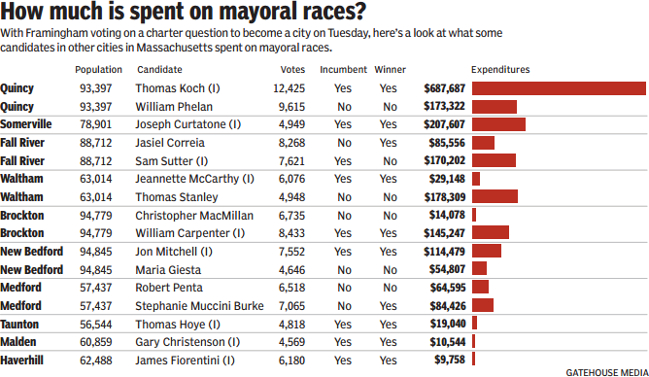

Mitchell’s campaign spending topped $114,000, more than double his opponent, according to state records. He handily won the race, receiving about 62 percent of the vote.

Giesta said the experience demonstrated how difficult it can be for someone without money or a political pedigree to get involved in local politics.

“You know, I’m not wealthy,” she said. “I don’t come from a wealthy family, and it was very hard to come in and run and try to convince people that I was the best person for the job, and do it without a lot of money.”

While it’s hard to attribute any candidate’s loss to a single factor, Giesta’s experience illustrates a common belief: the candidate who spends the most money often wins.

As Framingham prepares for a historic decision Tuesday that could usher in a new city form of government, critics have focused on the role of money in politics to argue against the change.

They fear that installing a strong mayor to head Framingham’s executive branch could fundamentally change the nature of politics in the community, replacing volunteers who win office with the support of their neighbors with well-financed political operatives.

While money doesn’t always guarantee victory in politics, a study of the 2015 mayoral races in Massachusetts suggests it certainly helps. In 24 contested elections that year, the top spender won 75 percent of the time, according to a study produced by the state’s Office of Campaign and Political Finance.

Median spending on mayoral campaigns has also generally increased since OCPF began studying the subject in 1997, though the increase was not dramatic or consistent. The median spending figure for candidates competing in the general election stood at $27,127 that year. It topped $30,000 in both 2013 and 2015, according to OCPF.

Incumbent Quincy Mayor Thomas Koch spent the most to defend his seat in 2015, dropping more than $687,000 to defeat former mayor William Phelan in a race that dwarfed others in the state that year in expenditures.

As the field of candidates in Quincy began to take shape that year, resident Charles Dennehey Jr. considered throwing his hat into the ring. Dennehey, a fiscal conservative who retired from a career in financial services, said he was unimpressed with the city’s last three mayors.

While he spent time gathering signatures to get on the ballot, Dennehey said he soured on the process when donors began to approach him. Contractors, real estate agents and others who do business in Quincy asked where to send the money, Dennehey said.

“I thought about it and I realized I’m not a politician, and to be a politician, you’ve got to be for sale,” he said.

It’s not always the case that the top spender wins the race. In Waltham, incumbent Jeannette McCarthy fended off a challenge two years ago from Thomas Stanley, who outspent her six-to-one, dropping more than $178,000 on the race.

Brian Arrigo spent less than $90,000 in his successful 2015 bid to unseat incumbent Revere Mayor Daniel Rizzo, who poured close to $250,000 into the race. In the end, the candidates were separated by only 108 votes after a recount.

While he didn’t prevail, Rizzo said the race was complicated by external factors, including the city’s then-pending lawsuit against casino developers. Rizzo, who is mounting another run for city council, said money undeniably plays a role in winning office.

“As much as knocking on doors and holding signs and displaying bumper stickers and lawn signs can be helpful … it still costs money to get your mailings out,” he said, “to take ads in newspapers and to do other things that are necessary to spread your message and to get your face in front of as many people as you can, and as often as you can.”

In Marlborough, a competitive race can top $60,000, said Mayor Arthur Vigeant, who is gearing up for re-election in the fall. Vigeant said it costs as much as $5,000 to send mailings throughout the city.

For his part, Vigeant said he doesn’t rely on the power of incumbency; the longest any mayor has served in Marlborough is six years, said Vigeant, who is poised to break that streak if he wins in November.

“I know that sentiment can turn on a dime,” he said, “and it’s usually not the big things. It’s the small things that people get upset about.”